Archive

Negative equity is disproportionately concentrated in the Chicago region’s communities of color, Woodstock Institute report shows

Tom Feltner | Vice President

Tom Feltner | Vice President

Woodstock Institute

Homeowners with mortgages in African American communities more than twice as likely to be underwater as homeowners in white communities

CHICAGO–Negative equity is disproportionately concentrated in the Chicago region’s African American, Latino, and majority minority neighborhoods, a new report from Woodstock Institute found. The report also found that borrowers in communities of color have much less equity on average than do borrowers in predominantly white communities.

View the full report here: http://bit.ly/strugglingtostayafloat

Join us for a telephone briefing Tuesday March 27 at 10am CT: http://stayingafloat.eventbrite.com/

The report, “Struggling to Stay Afloat: Negative Equity in Communities of Color in the Chicago Six County Region,” used data from a major provider of mortgage and home value data to examine patterns of underwater homes in communities of various racial and ethnic compositions in the Chicago six county region in 2011. It found that:

- Nearly one in four residential properties in the Chicago six county region is underwater, with just under $25 billion of negative equity. The average underwater property has 31.8 percent more outstanding mortgage debt than the property is worth.

- Borrowers in communities of color are much more likely to be underwater than are borrowers in white communities.

- Borrowers in communities of color are more than twice as likely as are borrowers in white communities to have little to no equity in their homes. In highly African American communities in the Chicago six county region, 40.5 percent of borrowers are underwater, while another 5.4 percent are nearly underwater. Similarly, 40.3 percent of properties are underwater in predominantly Latino communities and 5.3 percent are nearly underwater. In contrast, only 16.7 percent of properties in predominantly white communities are underwater, with another 4.4 percent nearly underwater.

- Almost three times as many properties in communities of color are severely underwater compared to properties in white communities. In predominantly African American communities, 30.1 percent of properties have loan-to-value (LTV) ratios—a comparison of outstanding mortgage debt to home value—exceeding 110 percent, while that figure is 30 percent in predominantly Latino communities. In contrast, just 10.1 percent of the properties in predominantly white communities have LTVs exceeding 110 percent.

- Borrowers in communities of color have much less equity in their homes than do borrowers in white communities, resulting in a significant wealth gap.

- Only about one-third of homeowners in communities of color have significant equity in their homes. In predominantly African American communities, 34.5 percent of borrowers have more than 25 percent equity in their homes, while 33.1 percent of borrowers in Latino communities have more than 25 percent equity in their homes. Fifty-five percent of borrowers in predominantly white communities have more than 25 percent equity.

- Borrowers in communities of color have much higher average loan-to-value ratios than do borrowers in predominantly white communities. The average LTV ratio is 92.1 in predominantly African American communities and 87.4 in Latino communities, compared with an average LTV ratio of 67.7 in predominantly white communities.

Negative equity contributes to community decline by potentially leading to increased foreclosure activity, threatening the success of foreclosure prevention programs, and draining neighborhood wealth. In addition, the destruction of assets caused by negative home equity may disproportionately threaten the economic security of people of color because home equity is a larger proportion of their net worth than it is for white people.

View the full report here: http://bit.ly/strugglingtostayafloat

The report concluded with a number of policy recommendations to reduce the negative impacts of concentrated negative equity, including:

- Servicers should use principal reduction as a foreclosure prevention tool more broadly.

- The Federal Housing Finance Authority should permit loans backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to be eligible for principal reductions.

- Servicers should streamline processes for short sales.

—

Tom Feltner | Vice President

Woodstock Institute

29 E Madison Suite 1710 | Chicago, Illinois 60602

T 312/368-0310 x2028 | F 312/368-0316 | M 312/927-0391

www.woodstockinst.org | tfeltner@woodstockinst.org | @tfeltner

Related articles

- A good credit score did not protect Latino and black borrowers (scoppcanton.wordpress.com)

- Negative Equity Increasing Around US; but Not Oro Valley (finehomesdigest.wordpress.com)

- Housing Still Drowning in Underwater Mortgages (blogs.wsj.com)

EPI News: Today’s labor market – Mixed signals

The latest assortment of government data tells different stories about the strength of the economy, providing no guarantee that we are yet experiencing a self-sustaining, robust jobs recovery.

The good news: State-level data show signs of recovery

State-level data released this week by the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that most states have been experiencing the steady progress towards economic recovery seen nationally. Over the four-month period from October 2011 to January 2012, every state except New York experienced a reduction in its unemployment rate. Over the course of a year (from January 2011 to January 2012), seven states experienced job growth exceeding 2.0 percent, while North Dakota experienced growth of 5.7 percent. Notably, five states (Alaska, Mississippi, Missouri, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) lost jobs over this period, led by Wisconsin’s loss of 12,500 jobs. (Click here for interactive state maps.)

Despite these generally positive trends, four states and the District of Columbia have unemployment rates at or above 10.0 percent (led by Nevada at 12.7 percent), while 11 states plus the District of Columbia have unemployment rates of 9.0 percent or higher.

“States looking to further spur economic growth should invest more significantly in infrastructure, such as transportation networks, schools, and broadband, while avoiding budget cuts that would impede economic recovery today and could compromise future economic prosperity,” wrote EPI’s Douglas Hall, director of the Economic Analysis and Research Network.

The not-so-good news: Low level of voluntary quits should temper recent optimism about the labor market

Through examining voluntary quits, this week’s Economic Snapshot provides further evidence that the country’s labor market is not yet out of the woods. Voluntary quits, defined as workers who voluntarily leave their jobs, are high when job opportunities are plentiful and employed workers have the flexibility to look for jobs that pay better and more closely match their skills and experience. During downturns, on the other hand, the number of voluntary quits drops as job opportunities become scarce. The Snapshot shows that the number of voluntary quits is still more than 30 percent below the pre-recession level—and has seen no improvement since last summer.

More of the same: Job-seekers ratio remains unchanged

Finally, Tuesday’s release of the latest Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed decreases in both job openings and hires in January. However, the job-seekers ratio—the ratio of unemployed workers to job openings—was 3.7-to-1 in January, unchanged from the revised December ratio.

“The softness in January’s job openings is inconsistent with the strength of January’s employment and unemployment report,” explained EPI labor economist Heidi Shierholz. “These inconsistencies underscore that it is too soon to declare that we have entered a self-sustained period of robust job growth.”

Brad Plumer of the Washington Post cited Shierholz’s analysis for his Wonkblog piece “Why are wages still stagnant? Blame the labor market”:

“There are still 3.7 job seekers for every available employment opportunity. That’s down considerably from the brutal 6.7-to-1 ratio seen in July, 2009. But as Heidi Shierholz of the Economic Policy Institute points out, the current ratio is also higher than at any point during the 2001 downturn. Across just about every industry, competition remains intense for a limited number of jobs, which means that employers are under less pressure to offer higher pay in order to entice prospective workers.”

EPI in the news

Shierholz’s analysis of last Friday’s release of the Employment Situation Summary by the Bureau of Labor Statistics was also picked up by multiple national media outlets, including the Washington Post, NPR, McClatchy, Huffington Post, and CNBC.

- Speaking to NPR’s Scott Neuman, Shierholz explained why the labor market still needs to gain many more jobs to return to its pre-recession health, and why it’s difficult to predict when this will occur. “We don’t have some historical perspective to compare this to and go, ‘OK, we know from experience that when the unemployment rate gets to X, or the number of jobs gets to whatever, that’s when people will start coming back,’” she said.

- And Shierholz told the Huffington Post’s Lila Shapiro that although we are seeing job growth, “it’s still a hellish job search out there” for job seekers.

EPI President Lawrence Mishel’s latest research on young workers’ declining wages continues to inform the national economic conversation. Mishel’s findings were most recently cited by the New York Times,CBS News, Huffington Post, and Think Progress.

- From the New York Times editorial “Better Numbers on Jobs”:

“Years into a weak labor market, and with years to go before full recovery, the scars are becoming all too apparent. Recent data from the Economic Policy Institute shows that the inflation-adjusted hourly wage of college-educated men aged 23 to 29 dropped 5.2 percent from 2007 to 2011, and for female college graduates of the same age, 4.4 percent. Joblessness and wage declines are also pronounced for those with only a high school education. For those men aged 19 to 25, wages fell 8 percent from 2007 to 2011. For those young women, the decline was 3.1 percent.” - CBS News’ MoneyWatch: “Recent college graduates have had a hard time landing jobs and those that have jobs, are earning less. The Economic Policy Institute found that the average inflation-adjusted hourly wage for male college graduates aged 23 to 29 dropped 11 percent over the past decade. For female college graduates of the same age, the average wage is down 7.6 percent.”

- Huffington Post: “A new analysis from the Economic Policy Institute shows what a lot of younger Americans have probably noticed for themselves: even if you’re lucky enough to have a job, it’s still tough to get ahead. Over the last decade, wages for younger male college grads have plummeted by 11 percent, while women college grads saw their paychecks drop by 7.6 percent.”

- And Think Progress: “Not only has the Great Recession been bad for workers entering the workforce, but as the Economic Policy Institute noted, the entire last decade has essentially been lost in terms of entry-level wages.”

Art, Culture, and Community Development Collaboratory Begins Research in New Orleans

Reposted from: Imagining America: Artist and Scholars in Public Life

Posted on March 5, 2012 by Jeremy Lane

By Micah Salkind, Doctoral Student in American Studies, Brown University, Catherine Michna, PhD, Instructor, University of Massachusetts, Boston, and Ruth Janisch Lake, Assistant Director, Civic Engagement Center, Macalester College

IA’s Art, Culture, and Community Development Collaboratory spent Martin Luther King, Jr. Day weekend in New Orleans working on the first phase of our participatory action research. We documented and interviewed participants from several IA member institutions’ civic engagement programs and cultural partnerships in that city. We began at Xavier University, where longtime professor (and IA board member) Ron Bechet explained how the Xavier Art Department’s longstanding cultural partnerships with artists and community organizers shape his institution, affect his collaborators, and contribute to cultural life in the city.

Bechet introduced us to Big Chief Darryl Montana of the Yellow Pocahontas Mardi Gras Indians, who has been working with the Community Arts Program at Xavier since 1997, developing Mardi Gras Indian Arts (MGIA) education and youth programming for middle-school children. According to Montana, the longstanding partnership between Mardi Gras Indian practitioners and Visual Arts Professors Bechet and MaPó Kinnord-Payton has helped to facilitate a growing recognition of Mardi Gras Indian art and performance as the “heartbeat” of New Orleans’ cultural landscape.

In 2007, the three created an intensive hands-on cultural immersion and training program for middle school age children from Xavier’s Gert Town neighborhood and greater New Orleans. Each summer since 1997, youth have learned how Mardi Gras Indian traditions developed while acquiring costume-making skills. Beginning this year, the program will take place year-round since Xavier has expanded its support for MGIA into a continuous component of its community arts curriculum.

For Montana and the Yellow Pocahontas tribe, MGIA is a platform to develop organizing and pedagogical strategies around intellectual property issues that affect their artist communities and city. Cultivating long-term engagement through MGIA is part of Xavier’s complementary commitment to educating its own students and Gert Town youth, about ways that elites, throughout the city’s history, have profited in unethical ways from black working class culture. The MGIA program is itself an ethical practice that models ways of acknowledging and supporting black cultural production by supporting the communities that cultivate and share it.

Reflecting on the role of the MGIA and similar programs at Xavier, Bechet noted the importance of university/community cultural partnerships to New Orleans’s recovery from Hurricane Katrina: “You can see it one individual at a time.” For example, when Xavier contributed financially so Darryl Montana could come home and rebuild his house, “he had an ability to help the next generation … individuals [like him] have taken on the responsibility of passing on the values of this place and what’s important about it to them.” We saw an example of such locally-grounded, collective-minded values first hand when we visited Xavier’s newest partner, Jenga Mwendo, founder of the Backyard Gardener’s Network (BGN). BGN’s “Guerrilla Gardeners” project in the Lower Ninth Ward not only directly works to address the problem of “food deserts” in African American neighborhoods, but also facilitates discussions between community members, city leaders, and student volunteers about the role that gardening plays in community building and neighborhood revitalization in the post-Katrina city.

Reflecting on the role of the MGIA and similar programs at Xavier, Bechet noted the importance of university/community cultural partnerships to New Orleans’s recovery from Hurricane Katrina: “You can see it one individual at a time.” For example, when Xavier contributed financially so Darryl Montana could come home and rebuild his house, “he had an ability to help the next generation … individuals [like him] have taken on the responsibility of passing on the values of this place and what’s important about it to them.” We saw an example of such locally-grounded, collective-minded values first hand when we visited Xavier’s newest partner, Jenga Mwendo, founder of the Backyard Gardener’s Network (BGN). BGN’s “Guerrilla Gardeners” project in the Lower Ninth Ward not only directly works to address the problem of “food deserts” in African American neighborhoods, but also facilitates discussions between community members, city leaders, and student volunteers about the role that gardening plays in community building and neighborhood revitalization in the post-Katrina city.

On Saturday, led by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Professor and Interim Associate Vice Chancellor Cheryl Ajirotutu, we participated in UMW’s annual reception for their New Orleanian community partners at the U.S. Mint Museum. We met UWM students and administrators and had the chance to interview a wide range of UWM’s local partners, who have been collaborating on the University’s winter term course in New Orleans since 2005. We also enjoyed zydeco piano playing by UWM partner, Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes.

On Saturday, led by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Professor and Interim Associate Vice Chancellor Cheryl Ajirotutu, we participated in UMW’s annual reception for their New Orleanian community partners at the U.S. Mint Museum. We met UWM students and administrators and had the chance to interview a wide range of UWM’s local partners, who have been collaborating on the University’s winter term course in New Orleans since 2005. We also enjoyed zydeco piano playing by UWM partner, Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes.

Later in the weekend, we joined Barnes and UWM, Xavier, and Macalester groups at the Vietnamese Initiatives in Economic Training (VIET) Center in New Orleans East where we participated in VIET’s annual Martin Luther King Day of Service. There we met Cyndi Nguyen, VIET’s Executive Director, and saw and heard about VIET’s thriving community health and cultural/economic development programs for youth and elders. Both the Macalester College students enrolled in the New Orleans and the Performance of Urban Renewal course and the UMW students working towards degrees in social work, as well as those who are taking Professor Ajirotutu’s cultural history course in New Orleans, prepared for their service at VIET by viewing and discussing the film “A Village Called Versailles,” a documentary on the inter-generational, faith-based community organizing of New Olreans’ Vietnamese community, which was not only affected by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, but also by a new government-imposed toxic landfill.

The group from Macalester College included 12 first year Bonner Community Scholars enrolled in a course titled, “New Orleans and the Performance of Urban Renewal,” which was co-taught by Ruth Janisch Lake (collaboratory member) and Molly Olsen. This intensive J-term (January interim) course assumed a human-centered, arts-based urban studies perspective on the continued efforts of New Orleans to restructure and redefine itself in the 21st century amidst various ecological, economic and political challenges. The course provided students with the essential critical, historical, and cultural framework through which to interpret various site visits and civic engagement projects with local artists, activists, and scholars in New Orleans. This was the seventh Macalester group that Civic Engagement Center staff member Ruth Janisch Lake has brought to New Orleans since January 2006.

Our team members interviewed several Macalester Bonner Community Scholars about their program’s practices of community-based learning and civic engagement. During their seven days in the city, the Macalester group connected with a Community Arts class with Ron Bechet and also learned more about New Orleans historical and ethnic geography with Tulane University Professor Richard Campanella. They visited Backstreet Cultural Museum in Tremé and this year participated in a second line parade with the Undefeated Divas in Central City. They also meet with a range of non-profit organizations and community leaders as they discussed issues of race and class in the city’s uneven recovery from Hurricane Katrina. As one Bonner student noted:

Our team members interviewed several Macalester Bonner Community Scholars about their program’s practices of community-based learning and civic engagement. During their seven days in the city, the Macalester group connected with a Community Arts class with Ron Bechet and also learned more about New Orleans historical and ethnic geography with Tulane University Professor Richard Campanella. They visited Backstreet Cultural Museum in Tremé and this year participated in a second line parade with the Undefeated Divas in Central City. They also meet with a range of non-profit organizations and community leaders as they discussed issues of race and class in the city’s uneven recovery from Hurricane Katrina. As one Bonner student noted:

The course definitely expanded my awareness and deepened my knowledge about the communities performing urban renewal in New Orleans. I loved the way the week was laid out and thought it was conducive to experiential, meaningful learning. We started the week off with a fascinating tour with Tulane Professor Rich Campanella and really appreciated the information he shared with us about NOLA’s ethnic and physical geography. Participating in the second-line parade gave me a powerful sense of the importance of having cultural traditions to return to when tragedies strike. Visiting Robert Green in the Ninth Ward was another influential experience, hearing about the ways in which he has advocated for and helped to rebuild his community post-Katrina. I also appreciated getting to visit the Vietnamese community in New Orleans East, and seeing how incredibly organized and resilient this largely youth-led community was in working towards positive change. Finally, I valued interacting with families whose homes we installed CFL light bulbs in through Project Green.

To round out our weekend of research and conversation, IA team members visited the Ashé Cultural Arts Center in Central City to participate in a night of singing celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday and to meet with students and faculty at Ashé’s new alternative college program—Ashé College Unbound (ACU). College Unbound began in Providence, RI, where IA Page Program Director Adam Bush worked with Big Picture Learning, a non-profit focused on developing internship-based curricula, and Roger Williams University’s School of Continuing Studies to create a student-centered bachelors degree program. In its first year, ACU has enrolled eleven students, primarily adult learners and longstanding community leaders, with a wide range of work experience and cultural development skills under their belts. The ACU student body works collaboratively with the organization’s advisory board and academic and community arts mentors towards a degree while matriculating in, and helping to create, semester-long workshops on housing, economics, culture, and education policy.

This spring, our collaboratory will produce a short video that will explore how these and other university projects have, in fact, become part of New Orleans’ cultural history by not only addressing historical inequity, but also by helping to create a new paradigm of the struggle for justice in the city. We also plan to create a white paper outlining some of the promising practices we see enacted in university/community cultural partnerships. Foregrounding how students have become more engaged, civic actors, as a result of their participation in these projects, we will also listen for different and surprising effects of their participation. We hope that the archival materials we create will be useful as scholars around the globe try to make sense of post-Katrina New Orleans.

This spring, our collaboratory will produce a short video that will explore how these and other university projects have, in fact, become part of New Orleans’ cultural history by not only addressing historical inequity, but also by helping to create a new paradigm of the struggle for justice in the city. We also plan to create a white paper outlining some of the promising practices we see enacted in university/community cultural partnerships. Foregrounding how students have become more engaged, civic actors, as a result of their participation in these projects, we will also listen for different and surprising effects of their participation. We hope that the archival materials we create will be useful as scholars around the globe try to make sense of post-Katrina New Orleans.

New Orleans is an amazing first case study, which we hope to complement with work in other cities and with other institutions affiliated with our working group. Current members hail from Holyoke, Baltimore, Minneapolis/St. Paul, Providence, Syracuse, and Milwaukee. This is just the beginning!

#

Photo credits: 1) University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Xavier University, and Macalester University students and the AC&CD collaboratory team at VIET’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service, by Ruth Janisch Lake; 2) Jenga Mwengo, Backyard Gardener’s Network; 3) Ron Bechet, Micah Salkind, and Catherine Michna at the University of Wisconsin Madison’s Thank You reception for their local partners, by Ruth Janisch Lake; 4) Macalester College Bonner Community Scholars learning more about the environmental and human geography of NOLA at the Irish Channel stop on the city tour with Professor Rich Campanella; and 5) Dr. Cheryl Ajirotutu with AC&CD videographers, Hubie Vigreux and Alejandra Tovar, by Ruth Janisch Lake

Income, Health, and Payday Deaths

Posted on March 1, 2012

Posted on March 1, 2012

It’s hardly news that poorer people have worse health on average – but teasing apart the link of income and health is harder. The income-health gradient could be because people lose income when they have health problems, or it could be due to common causes (e.g. education) rather than income itself. In fact, the relationship is more complex than you might guess; and having recently stumbled over three wonderful studies that help unpick this, I thought I’d share them with you and see what you thought.

Short-run effects: payday deaths

Probably my favourite of these studies is a lovely paper in press by Evans and Moore, using US data. Their reasoning is that if we want to know the SHORT-RUN impact of income and health, we can look at the first day of the month when most people get paid or receive welfare payments, and see if people are more or less likely to die on payday. The results are staggering.

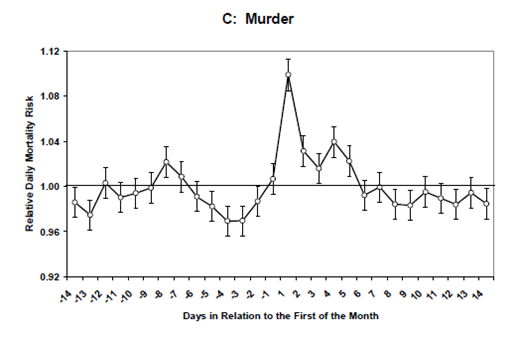

In the chart below, you can see how murder rates vary across the month. The relate daily mortality risk is about 10% higher on payday than it is for the rest of the month, and a little bit higher for 4 days after payday.

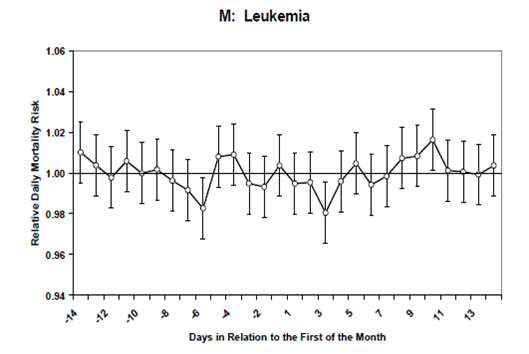

What’s particularly striking is that this is only found for causes of death that are related to drink in the short-term. So for example, if we look at leukemia deaths in the chart below, we see absolutely no change over the month at all.

In other words, people drink more on payday, and this raises the chances of them dying. Otherwise there’s no short-run impact of payday on health.

Long-run effects: lottery winnings

Does this mean that higher incomes are actually bad for health? Well, not so fast. The deaths-by-payday charts are good for showing the very short-run impacts of income on health, but they don’t show what happens to a change in permanent income, nor do they show the longer-run impacts. The best way of getting at the causal impact of income here is to look at lottery winnings, which (unlike most sources of income) are completely random within any particular lottery.

In the UK, a paper by Apouey & Clark 2009 looks at the impact of lottery winnings on health. Like Evans and Moore, they find that this source of extra income leads to more smoking and drinking (perhaps unsurprisingly, if you think about how you personally would spend a lottery winning (or me anyway), and also the fact that people who play the lottery are going to have a different attitude to risk than other people).

Yet we also see noticeable improvements in mental health among people who win on the lottery – suggesting that financial problems genuinely cause mental health problems.

The net effect of these two patterns in Apouey & Clark is that there’s no effect of lottery winnings on self-reported general health – but while self-reported health can be useful, it also has lots of problems as a measure. A more objective measure of general health is mortality, and for this we have to turn to some Swedish data analysed by Lindahl 2005 (free version here). Lindahl finds that about £1,000 worth of lottery winnings reduce the probability of dying by 2-3% over the next five years. With this design, it’s pretty unarguable that this shows a genuine causal impact of income.

Back full circle

So this takes us right back to where we started – poor people have worse health, and this is (at least partly) because lower incomes genuinely cause worse health. But through these three very nicely-designed studies, we get a glimpse into the complexity of this pattern across different aspects of health over different time periods – and it’s this that I thought made them particularly worth sharing.

Desperately Working to Stay Afloat

Marian Wright Edelman

Marian Wright Edelman

President, Children’s Defense Fun

Posted: 02/17/2012 5:20 pm

Levi Nation, age 12, and his sister Katherine, eight, eat Sunday dinners at their grandparents’ house in rural Kalkaska County, Michigan. They live with their parents, James and Lois, in an old trailer next door. Though both parents work, they can’t afford a better place—or health insurance or outings with the children. “Sometimes I wish we could go someplace like down to a water park or, like, the zoo,” Levi said.

At one time, the Nations owned a home. But like so many other American families, their standard of living has declined over the past decade even though they are a two-parent working family.

James’s family employment story echoes the Michigan story, as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Julia Cass learned when she met the family while on assignment for the Children’s Defense Fund. His father worked for General Motors in Flint until it offered him “a golden handshake and he took the check.” James said. James considers himself a member of “probably the last generation to be able to walk out of high school and get a decent job,” though he and his brother came too late to find well-paying work at GM and move up into the middle class.

During the earlier years of their marriage, when they were able to afford to buy a home, James and Lois lived in Durand, near Flint. He worked for 14 years in a family-owned machine shop that made tools for the aluminum wheel industry. Lois, who’d taken some junior college classes, worked as a bank teller. When Levi was born, she wanted a career she could base around a child’s schedule and went to a school for massage therapy. In 2004, they sold their house and moved to Kalkaska County, where Lois grew up. They wanted to raise their children in a safer place, and planned to live in a trailer on property Lois’s parents owned and build a home there later.

Levi Nation, age 12, and his sister Katherine, eight, live with their parents, James and Lois, in an old trailer in rural Kalkaska County, Michigan. Though both parents work, they can’t afford a better place—or health insurance or outings with the children. James says, “You can work your butt off and still not get ahead.”

Kalkaska and neighboring Grand Traverse County on Lake Michigan are, in part, resort areas with second homes and luxury condos. James started a handyman service and Lois had massage clients. “Then the economy kind of fell apart and I had to get a job to be sure the bills were paid,” James said. He worked as a mechanic at a farm equipment store for a few years and recently moved to a part-time job with the Village of Kalkaska as a wastewater operator. “It’s a little less money, but the commute is shorter, so it evens out,” James said. “Also, I’m hoping it will turn into a full-time job with benefits.” James earns $13 an hour and works 30 hours a week. He earns a little more than $19,000 a year.

Lois didn’t have enough clients in her massage business so she took a job at McDonald’s. “I’ve worked there four years and am just now breaking over the $8 an hour mark,” she said.

That job, too, is part-time. She says the company keeps hiring new people and spreading out the hours so that if someone leaves or doesn’t show up, they have other employees who can fill the shifts. “They think you can just come in whenever they need you, but a lot of people can’t do this because they have family,” she said. “My kids are too young to leave by themselves.” She works 15 to 25 hours a week and earns between $10,000 and $15,000, depending on how many hours she gets.

The family is working so desperately to stay afloat, Lois recently began training for a second part-time job at a credit union. She will be a fill-in person working from 20 to 30 hours a week and earning $8.50 an hour. The number of hours will vary from week to week at both jobs, but she expects to wake up at 3:30 a.m. to work at McDonald’s from 4:15 till 8 a.m. and to work at the credit union from late morning until 5 or 6 p.m. on Mondays and Fridays and half-days on Saturdays, the credit union’s three busiest days. “I’ll miss the kids’ soccer games,” she said, “but we need the money.” Because both jobs are part-time, she will receive no benefits.

Their children Levi and Katherine are covered by Medicaid, a critical safety net support for their family. But James and Lois make too much to be eligible for Medicaid themselves, but not enough to buy health insurance. James recently needed $2500 in dental work and Lois had $1200 in medical tests, for which they reluctantly used CareCredit cards; with this method, if they pay off the doctor and dental bills within 18 months, they pay no interest, but if they don’t, James said they will be charged 24 to 36 percent interest retroactive to date of service, adding, “We will pay them off somehow because we’ve worked hard to keep good credit”—to be able, someday, to get another home for themselves and their children.

The Nations receive about $80 a month in food stamps. When their children were younger they were eligible to attend Head Start. It helped a lot with the children’s development. “We couldn’t afford to pay for preschool, and if it hadn’t been for Head Start, we wouldn’t have gotten Levi diagnosed [with mild attention deficit hyperactivity disorder]. And the teacher taught me ways to work with him.” Katherine, she said, is going into third grade and already reads on the fifth grade level, “and they have to challenge her in math too because of Head Start. Every week they were sending something home on how to challenge your child’s brain and make it fun.”

Lois said they applied to Habitat for Humanity for a house but “they turned us down. They said we had more opportunities than other people because we have land and good credit.” James commented, “We’re kind of between a rock and a hard place” of being somewhat poor but not poor enough. “The way grocery and gas prices keep going up, I don’t see where we’re making that much money that we should be in between. You can work your butt off and still not get ahead.” For now, they keep going—not yet getting ahead, but working as hard as they can, and never giving up.

Follow Marian Wright Edelman on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ChildDefender

Related articles

- Marian Wright Edelman: Still Hungry in America (huffingtonpost.com)

Can Manufacturing Jobs Come Back? What Should We Learn From Apple and Foxconn

David Paul

David Paul

President, Fiscal Strategies Group

Posted: 02/13/2012 8:30 am

Apple aficionados suffered a blow a couple of weeks ago. All of those beautiful products, it turns out, are the product of an industrial complex that is nothing if not one step removed from slave labor.

But of course there is nothing new here. Walmart has long prospered as a company that found ways to drive down the cost of stuff that Americans want. And China has long been the place where companies to go to drive down cost.

For several decades, dating back to the post World War II years, relatively unfettered access to the American consumer has been the means for pulling Asian workers out of deep poverty. Japan emerged as an industrial colossus under the tutelage of Edward Deming. The Asian tigers came next. Vietnam and Sri Lanka have nibbled around the edges, while China embraced the export-led economic development model under Deng Xiaoping.

While Apple users have been beating their breasts over the revelations of labor conditions and suicides that sullied their glass screens, the truth is that Foxconn is just the most recent incarnation of outsourced manufacturing plants — textiles and Nike shoes come to mind — where working conditions are below American standards.

While the Apple-Foxconn story has focused attention on the plight of workers living in dormitories who can be summoned to their work stations in a manner of minutes, the story has also become part of the debate about whether the U.S. should seek to bring back manufacturing jobs or should instead accept the conclusions reached by some economists that not only does America not need manufacturing jobs, but it can no longer expect to have them.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz argued recently that our difficulties recovering from the 2008 collapse are a function of our migration from a manufacturing to a service economy. While this migration has been ongoing for years, Stiglitz has concluded that the trend is irreversible. His historical metaphor is the Great Depression, which he suggests was prolonged because the nation was in the midst of a permanent transition from an agrarian economy to manufacturing, as a revolution in farm productivity required a large segment of the labor force to leave the farm.

The problem with this deterministic conclusion that America can no longer support a manufacturing sector is that it seems to ignore the facts surrounding the decline that we have experienced. In his recent article, Stiglitz notes that at the beginning of the Great Depression, one-fifth of all Americans worked on farms, while today “2 percent of Americans produce more food than we can consume.” This is a stark contrast with trends in the U.S. manufacturing sector. Manufacturing employment, which approximated 18.7 million in 1980 has declined by 37%, or 7 million jobs, in the ensuing years. However, the increase in labor productivity over that timeframe — 8% in real terms — explains little of the decline. Unlike the comparison with agriculture, where we continue to produce more than we consume, most of the decline in manufacturing jobs correlated with the steady increase in our imports of manufactured goods and our steadily growing merchandise trade deficit.

The chart below, based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, illustrates the growth in personal spending on manufactured goods in the United States over the past three decades, and the parallel growth in the share of that spending that is on imported goods. These changes happened over a fifty-year period. Going back to the 1960s, we imported about 10% of the stuff we buy. By the end of the 1970s — a period of significant declines in core industries such as steel and automobiles — this number grew to over 25%. As illustrated here, the trend continued to the current day, and we now import around 60% of the stuff we buy.

Over the same timeframe, as illustrated below, the merchandise trade deficit — the value of goods we import less the value we export — exploded. By the time of the 2008 collapse, the trade deficit in manufactured goods translated into 3.5 million “lost” jobs, if one applies a constant metric of labor productivity to the value of that trade deficit.

This is where Stiglitz’ comparison with the Depression era migration from an agrarian economy breaks down. As he duly notes, the economics of food production has changed, and today America’s agricultural sector feeds the nation and sustains a healthy trade surplus as well, with a far smaller share of the American workforce. In contrast, the decline in manufacturing jobs reflects the opening of world labor markets. Unlike agriculture, we are not self-supporting in manufactured goods, we have simply decided to buy abroad what we once made at home.

This shift has been embraced across our society. For private industry, outsourcing to Asia has been driven by profit-maximizing behavior and the pressures of surviving in competitive markets. For consumers, innovations in retail from Walmart to Amazon.com have fed the urge to get the greatest value for the lowest price. And for politicians — Democrats and Republicans alike — embracing globalization was part of the post-Cold War tradeoff: We open our markets, and the world competes economically and reduces the threat of nuclear conflict.

The notion that American industry, consumers and politicians were co-conspiring in the destruction of the American working class was a discussion relegated to the margins of public discourse, championed among others by union leaders, Dennis Kucinich on the left, Pat Buchanan on the right and Ross Perot, while largely dismissed by the mainstream media.

While Apple has been pilloried from National Public Radio to the New York Times for its effective support of a slave economy, most electronics consumer goods are now imported. The irony of the Apple story is that the Chinese labor content may well not be the cost driver that we presume it to be. As in many other industries, the costs of what is in the box can be a relatively small share of total costs, when product development, marketing, packaging and profits are taken into account.

This, of course, is why China is not particularly happy with their role in the Apple supply chain. When the profits of Apple products are divided up, far more of it flows to Cupertino than to Chengdu. And that is the reality of modern manufacturing. Based on National Science Foundation data on the value chain of the iPad, for example, final assembly in China captures only $8 of the $424 wholesale price. The U.S. captures $150 for product design and marketing, as well as $12 for manufactured components, while other nations, including Japan, Korea and the Taiwan, capture $76 for other manufactured components.

If anything, the NSF data — and China’s chagrine — reflect a world in which the economic returns to design and innovation far exceed the benefits that accrue to the line workers who manufacture the product. This is one part of the phenomenon of growing inequality, and would seem to mitigate the complaint that is often made that America no longer “makes things.” We may not make things, but we think them up and as the NSF data suggests, to the designers go the spoils.

Yet there is no fundamental reason that the decline in manufacturing jobs in America should be deemed inevitable and permanent. For all the talk about the number of engineers in China, the fundamental issue remains price. As a friend who is a consulting engineer who works with Apple in China has commented, “Yeah, they have engineers, but the driver is cost, cost, cost. And the labor quality is awful. We lose a lot of product and have to stay on top of everything, but at $27 per day, you can afford a lot of management.”

This argument conflicts with Stiglitz deterministic thesis. Just as manufacturing jobs left the United States, they can come back as economic conditions change. As wage rates rise in other countries, one competitive advantage of outsourcing shrinks. And if nations — from China to Taiwan — migrate away from their practice of pegging their currencies to the dollar, foreign currency risk exposure will offset some of the cost advantages of outsourcing. And today, as newly industrialized nations like Brazil have seen their own manufacturing sectors ravaged by mercantilist competitors, there is a growing understanding for the need for order and fair rules to govern the forces of globalization.

The Apple-Foxconn affair spooked consumers of Apple products — at least for a news cycle or two. Like Claude Rains in Rick’s Cabaret, we were shocked to confront the reality of labor conditions in China. But the story was less about China than about us. That Foxconn could put eight thousand workers to work within thirty minutes to accommodate a last minute design change by Steve Jobs was not — as Jobs suggested in a meeting with President Obama — an argument for why those jobs could never come back to America, but rather it was illustrative of the astonishing narcissism of the Apple world.

It is true, no American factory could deliver for Apple as Foxconn did. But on the other hand, there really was no need to. That story was less about what Foxconn could deliver than what Foxconn’s customer had the audacity to demand.

This story raised the question of whether we care where our products are made. The answer is unclear, however many Americans have long cared about purchasing cars made in this country, and Clint Eastwood’s Super Bowl ad has raised awareness of this question. What is clear is that if Americans care about where their products are made, companies will care. Therefore, even as the president promoted tax credits for insourcing — the new word for bringing those jobs back — perhaps another step would be to build on the power of choice. Perhaps not all Americans care where their products are made, but many certainly do. But even if one does care, it tends to be difficult to find out.

Perhaps a simple step would be for companies to provide that information to consumers. Even if it was voluntary labeling, knowing who chose to provide information to their customers would tell many of us all we need to know. Then we could find out whether the Apple story really changed anything, and whether consumers might be willing to take more into account that the last dollar saved if it enables us to sustain a diversified economy into the future.